Top Ten Myths of Third-party Inspection

Misunderstanding of third-party inspection is caused by hidden knowledge gaps and not limited to inexperienced personnel.

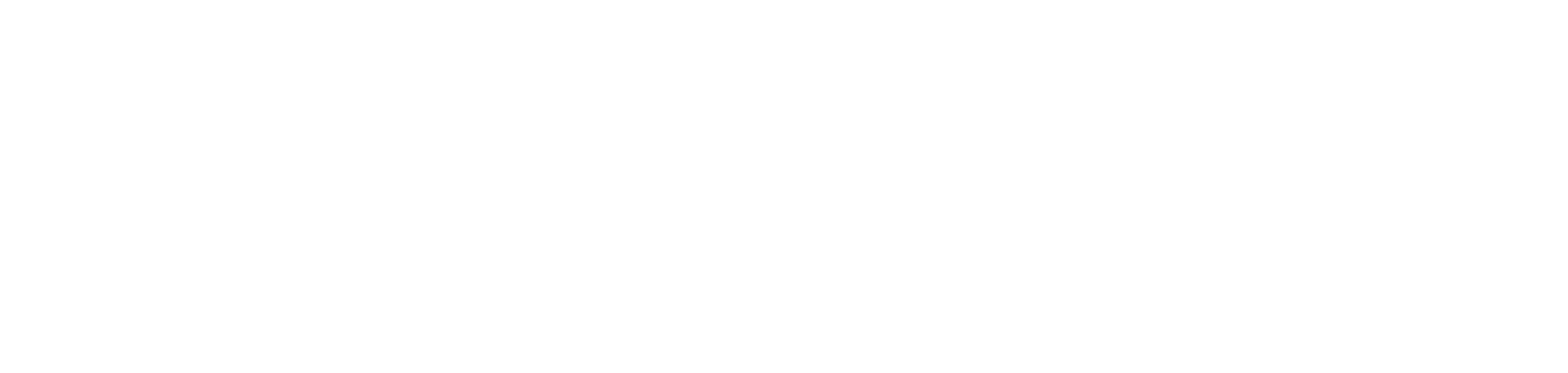

Third-party inspection (inspection) is a strategy used by capital projects in energy and other sectors to ensure suppliers’ equipment and materials are delivered complete, correct, and on-time. This is also referred to as source surveillance, vendor surveillance, or visual inspection. See inset for a definition of inspection.

The resources employed for inspection are usually contracted personnel, retained by the engineering and procurement (EP) company through an inspection agency (hence, third-party). The inspector may be referred to as the quality surveillance representative (QSR) or the third-party inspector (TPI or inspector).

Many inspection agencies, such as ACES Global Quality Services, Applus+, Caliper Inspection, Intertek, Killick Group, RINA, and SGS Canada Inc., offer local inspection services on a world-wide basis for coating, electrical and instrumentation, insulation and refractory, mechanical, rotating equipment, welding, and other disciplines. Many other inspection agencies, such as International Quality Consultants Ltd., Pro Inspection Ltd., and Vision Integrity Engineering Ltd., offer these services for specific disciplines or in specific areas.

Related Fact Sheet: Top 12 Myths and Facts About Third-party Inspection

Introduction

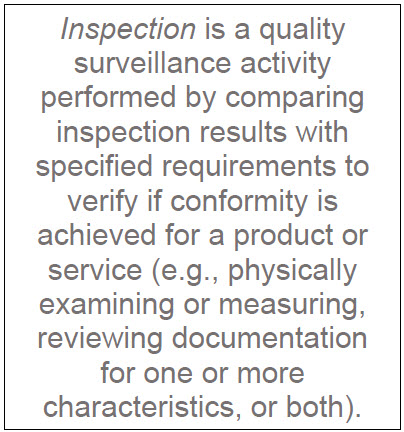

How often and what inspection services are performed are usually identified in the project execution plan (PEP), project procurement plan (PPP), supplier quality surveillance (SQS) plan, other documents, or a combination. While SQS is integral to many projects and typically part of the procurement or supply chain management (SCM) group, inspection is not a well‑understood function: there are many pervasive myths about its methods, objectives, and strategies. See inset for a definition of SQS.

These misunderstandings, unfortunately, are not limited to inexperienced personnel. These myths are often also believed by management and technical personnel who should know better. This is not because they are apathetic, not knowledgeable, uneducated, or unprofessional – far from it.

This is because projects have hidden knowledge gaps: the project management body of knowledge (BOK) and SCM BOK do not contain any detailed information or how-to guidelines for SQS. Further, the SQS BOK is not published; it is only available as propriety intellectual property (IP) and tribal knowledge. See inset for a definition of BOK.

This article identifies and explains the top 10 inspection myths. These myths, which may be encountered on any project, are presented in no specific order:

- Inspection is a quality assurance/quality control function.

- Inspection removes liability.

- Inspection can be set-up ad hoc or as needed.

- Inspection resources are available whenever and wherever required.

- Inspectors are immediately available to a project.

- Inspection expertise is always readily available.

- The inspector has immediate access to all the procurement and supplier documents.

- An inspector’s acceptance of documentation or inspection results is final.

- Inspection activities are limited to requirements identified in the inspection requirements document or inspection and test plan.

- Inspection is a one-size-fits-all solution.

- (Supplemental) Project managers are knowledgeable about inspection.

- (Supplemental) Supply chain managers or procurement managers are knowledgeable about inspection.

Related: This article uses best practices for describing abbreviations and acronyms. For more information see the ebook: Successful Projects Need Effective Communication.

1. MYTH: Inspection is a quality assurance/quality control function

SQS provides a risk management function, not a quality management function (e.g., it is not an ISO 9001, Quality Management Systems — Requirements program). Risk mitigation involves decreasing the probability of a negative risk occurring and protecting project objectives from impacts of negative risk. For a project, risk is that equipment and materials will be delivered incomplete, incorrect, or late.

Quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) has many interpretations because of the multiple definitions of assurance and control. QA/QC usually refers to the actions performed by the EP or supplier to ensure the quality of their processes, products, or services are satisfactory. Inspection is performed by the EP on the supplier’s deliverables before shipment.

Inspection is like insurance. The client (i.e., project owner) or project team, or a combination decides how much inspection is needed or not needed. It is possible to have too little or too much inspection. Projects use a cost‑benefit analysis to determine project risk tolerance, which typically determines how much inspection is needed and the cost.

FACT: The acceptable level of risk varies and depends on the cost benefit analysis, type of project, and other factors.

2. MYTH: Inspection removes liability

Neither the inspection agency nor inspector assume any responsibility for the contents or quality of the EP’s procurement documents or the supplier’s deliverables. See inset for a definition of procurement documents.

An inspector is assigned to perform activities, which are the quality verification points (QVPs) identified in the inspection requirements document (e.g., Section 4 of a purchase order) and the supplier’s inspection and test plan (ITP). This may entail hours or days of effort compared to the hundreds or thousands of hours consumed, and thousands of megabytes or pages of documentation produced by the EP and supplier. See inset for a definition of a QVP.

Inspection cannot ensure that supplier facilities, procedures, and products are error‐free or perfect because this is neither possible nor reasonable. No facility is error‐free or perfect.

Further, third-party inspection does not offer any additional or higher level of assurance that deliverables will be complete, correct, or on-time. In fact, the same inspection could be performed by third-party, second-party (i.e., EP), or first‑party (i.e., client) resources, or a combination, with the same results.

Indeed, any or all these parties may be involved in an inspection. For example, a witnessed performance test for a pump may be attended by the EP responsible engineer alone. Or, it may be attended by a team including the inspector, EP responsible engineer(s), client engineer(s), and others (e.g., commissioning or operations personnel).

Sometimes the supplier may be busy or lazy; thus, no quality control (QC) examination is performed on the materials and workmanship. The QC manager may claim that completed welds have been examined and accepted. However, when the inspector begins the examination, it will become immediately apparent to the inspector that the welding pick-ups and QC were not performed at all! For example, an examination of the welding completed by the nightshift crew (known for their lack of diligence and loose interpretations of acceptance criteria) revealed that numerous defects were not reworked. This means that arc strikes, incomplete fusion, incomplete penetration, lack of fusion, porosity, slag inclusion, spatter, and undercut must be marked, reworked, and re-examined.

Why does this matter? The nightshift’s lack of QC and poor workmanship requires that the inspector perform the supplier’s QC or reschedule the visit. Consequently, the inspector may take additional time to examine the welds, and document and discuss the defects with the QC manager. Then, they must return later to perform another examination to verify acceptability. Because of the inspector’s lack of trust in the crew’s workmanship and the QC manager’s word, the inspector’s second examination will likely be detailed and thorough to ensure all defects were reworked. Similarly, if they were not, then a third inspection visit may be required if the defects cannot be re-worked immediately. These extra activities add additional burdensome and unnecessary project expenses.

FACT: The purpose of inspection is to selectively determine compliance during production; not to ensure supplier deliverables are perfect or perform their quality control, or offer protection from liability.

3. MYTH: Inspection can be set-up ad hoc or as needed

Capital project execution takes months and years to complete. Therefore, inspection activities should be planned from the beginning during the detailed engineering phase.

The inevitable change-out of personnel as the project mobilizes and demobilizes, long timelines from material requisition (MR) to delivery of equipment and materials at site, and upfront procurement of long lead equipment all mean that by the time inspection is required at a supplier’s facility, significant project resources have already been expended.

It is problematic for inspection to identify issues with an EP or supplier’s scope of work when the equipment or materials are finally examined. An inspector will ask these questions, which often yield very expensive, inconvenient, or undesirable responses:

- Has this deviation or manufacturer been approved or is it a non-conformance?

- What does this specification or technical note requirement mean?

- Which specification or technical note has precedence?

- Will products produced to an alternative standard be acceptable?

- Who is responsible to supply a deliverable identified in the scope of supply?

- Why does the approved drawing or ITP not identify project requirements?

Inspection can be set-up ad hoc or as needed ONLY IF there is an emerging or new issue that needs an on-site examination. This provides the project with invaluable and objective information about the situation and what may be needed for a resolution (i.e., corrective or preventative action, or a combination).

FACT: When inspection is properly planned it is more effective and value-added because problems are identified and corrected before significant related impacts occur (e.g., errors occur on paper instead of during production).

4. MYTH: Inspection resources are available whenever and wherever required

A project comprises months of activities, and thousands EP and supplier hours. Availability of resources varies greatly on every project.

An Example

Pump inspection requirements may be established – somewhere and at some time. But personnel are busy and there are too many challenges to consider everything right now. It is difficult to determine what is required next week – let alone next month! Suddenly, the pump supplier notifies the project that an inspector is needed in Madison, Wisconsin next Monday morning! The project specified a hold point (this is the same as an API witness point) for a pump performance test. Oops. This oversight may impact the schedule and cause unavoidable expenses.

The project has an inspection agency that can provide inspection resources, so this may not be a problem. The SQS coordinator contacts the agency to inquire about inspector availability for an assignment at the pump supplier’s facility. Sure, they have two suitable inspectors and can provide resumes quickly. But this weekend is a national holiday; many personnel cannot be reached because they are already on holidays. So, the agency reaches out to their resources hoping for quick responses.

First, the good news. There are two suitably-qualified candidates.

Then, the bad news. The local candidate is already booked next week; the other lives 600 km (375 mi.) away. If the available inspector can reschedule their other responsibilities and the project is willing to incur their travel expenses, they could witness the test. Oops again.

Then, an inspection assignment must be issued – with a budget for costs. Should the inspector fly-in and rent a vehicle for a day, or use their personal vehicle? What about hotel and meal costs? The cost for these inspection services and expenses would typically be about CAD$ 3,200.00 (USD$ 2,500.00).

Wait a minute. The client purchased the exact same pump for another project last year! Is a witness of this test really required? Unfortunately, it is too late to waive the witness requirement because project approval would take at least one week (to collect all required approval signatures). Oops again. More savings avoided.

If the project waived the test, the cost of the inspection could be saved – but the supplier has already included the cost for the witnessed test in their price. There will be no cost savings (refund) for a change to a non-witnessed test. So, the project spends the money to witness the test, even though it may not be required.

FACT: Inspection resources may or may not be available. Inspection activities should be planned during detailed engineering – not when the services are needed.

5. MYTH: Inspectors are immediately available to a project

Project teams comprise dozens, hundreds, or thousands of personnel. Projects take months and years to execute from final investment decision (FID) to engineering and procurement, and to construction, commissioning, and start‑up. Inspectors are key team members, who are contractors hired through agencies. The project is a microcosm of daily activities, emails, and meetings and then – suddenly, the project needs an inspector for a few hours or days.

Typically, until the day the inspector is needed, the inspector is not involved with the project. They serve other clients and have assignments on other projects. They are not on-call or (as a colleague described it) waiting outside the project supplier’s facility with their laptop plugged into a current bush. If the project requests inspection services on short notice, the inspector may already be committed. The inspector’s schedule may or may not be flexible. Consequently, either the inspector or the project may be inconvenienced. A short‑notice request for inspector service is unprofessional, causes personnel to make mistakes (e.g., by scrambling and taking shortcuts), and assigning lower priority to other important tasks. With proper planning, all these challenges can be avoided.

A project may assume that travel time is of no consequence; however, in many areas, it is and can be significant.

An Example

It is possible for an inspector to visit two or three suppliers in one day in Calgary, Alberta mainly because many oil and gas (O&G) suppliers conduct business in the same industrial park in the city’s southeast. With a population of only 1.4 million, Calgary has sound road infrastructure and traffic is generally uncongested. But this is not the case in larger metropolises, such as Houston, Texas (7.2 million) or Los Angeles, California (13.1 million).

Moreover, an inspector working in Calgary, Alberta would typically use a personal vehicle to avoid the expense associated with hiring a taxi or renting a vehicle. Oftentimes, public transportation is not an option because routes to industrial sites are not adequately served. A personal vehicle permits agility and flexibility when scheduling inspection activities. The opposite may be true in other countries; if an inspector does not own a personal vehicle, alternatives include hiring taxis, renting vehicles, or using public transportation.

Travel time is prolonged if the inspector travels by air because additional time is required to:

- Travel to the airport, and park, if needed;

- Clear security and board the airplane;

- Travel in the air to the destination airport;

- Deplane and arrange ground transportation; and,

- Travel to the supplier’s facility.

After the inspection is complete, the above needs to be repeated in reverse. Travel expenses and time are chargeable and increase inspection service costs.

For a typical inspection visit, more time is needed than for the actual inspection activity itself. Thus, the total time required must be scheduled. For example, a one-hour inspection activity may require six hours of time and include:

- Two hours for administrative tasks such as assignment setup and review of procurement documents;

- Two hours for travel to and from the facility, waiting for a supplier representative, and for some contingency time; and,

- Two hours for inspection, report writing, and communication (e.g., emails and telephone calls or texts).

It is prudent to allow additional time for contingency (e.g., to manage a deficiency, for inclement weather, or time to navigate a large facility, find the items to be inspected, and perform the inspection). The example above includes one additional hour for contingency if the actual travel time is only one hour for a return travel distance of 75 km (47 mi.).

FACT: Like other busy professionals, inspectors have and keep tight schedules that are carefully planned.

6. MYTH: Inspection expertise is always readily available

Projects can usually secure the services of suitably‑qualified inspectors in the area local to the supplier’s facility. This is the case for suppliers in major O&G centres such as Edmonton, Alberta or Houston, Texas. It may not be the case, however, for suppliers in remote locations such as Lloydminster, Alberta or Painted Post, New York.

Mechanical and welding inspectors may be readily available in most areas. However, coating or electrical and instrumentation inspectors may be less available or unavailable, partly because they are less common. Thus, these inspectors may charge up to 50% more for their services when compared to mechanical and welding inspectors.

Sometimes it is necessary to assign two inspectors: one for each discipline. For example, an American Welding Society (AWS) or Canadian Welding Bureau (CWB) certified welding inspector and a National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) or Society for Protective Coatings (SSPC) certified coating inspector. But this is not always economical or possible. Occasionally (rarely), a dually-certified inspector is available. This versatile professional brings obviously beneficial cost savings to a project.

Assuming an available inspector can be found, what if the inspector has little discipline experience? What if the inspector is not a subject matter expert (SME)? Use these strategies to manage these shortfalls and leverage available cost-effective resources to satisfy project inspection needs:

- If possible, employ experienced and knowledgeable engineering and SQS personnel who can answer questions, and discuss requirements and results with the inspector. This may occur before the visit, during the visit, or after the visit to prepare or review the inspection report. Generally, inspectors in Canada are knowledgeable about Canadian codes and standards (in their discipline). Generally, inspectors from other countries have knowledge about Canadian codes and standards that varies and depends on experience;

- A project may require a certified inspector (e.g., AWS/CWB or NACE/SSPC) but occasionally the preferred choice is not available. For example:

• Only a senior certified inspector is available for a simple assignment; or,

• Only a junior certified or uncertified inspector is available for a complex assignment.

Address this challenge by using the method described in Item 1; - An experienced inspector may be available, but not have required discipline knowledge. This may be acceptable because they are still knowledgeable about codes, specifications, and standards, and know how to examine products, review test reports, and verify certifications. With these skills, the inspector can confirm that the supplier’s personnel and products are acceptable. For example, a welding inspector would be knowledgeable about coatings (and electrical equipment). External coatings in a dry climate are less critical than internal epoxy coatings in a severe service environment. Thus, it is standard practice for inspection of external coatings (e.g., galvanizing or paint) to be completed as part of the final inspection by a welding inspector;

- An experienced inspector will never tell the supplier what they do not know. The inspector will instead ask the supplier to explain work processes and demonstrate satisfactory results. Using this method, the inspector can verify product compliance and self-educate;

- Occasionally, there will be more than one assignment in the same area. Ideally, this work will be assigned to the same inspector to save costs. While there are minimal administrative savings in this scenario, there is a much more significant advantage – the inspector can build rapport with project and supplier teams. When an inspector inspects similar products (at the same or different suppliers), they become more knowledgeable about project requirements and specifications. If an inspector identifies a problem early, the lesson learned can be applied to ensure that there is no future recurrence. For example, the supplier overlooks that the project specification has more stringent acceptance criteria for non‑destructive examination (NDE) than the code of construction. After this requirement is identified, compliance can easily be verified during the review of subsequent NDE reports;

- An inspector’s report will include details of inspection activities, findings, and several photographs of materials, products, and workmanship. Typically, the inspector will acquire numerous photographs that can be provided upon request. But the inspector will only include the best – the clearest and most relevant photographs – in the report. The report may include attachments such material test reports (MTRs), non‑destructive examination (NDE) reports, or both. When the report is reviewed by the project team, it may be identified that the inspector was not aware of a possible problem (e.g., improper wiring materials and tagging). Photographs are an invaluable part of every report because they are usually unambiguous; and,

- Inspectors in Group of Seven (G7) or similar countries (e.g., South Korea) are usually able to communicate and report in English. In other countries, the inspection agency may need to use an English-speaking coordinator to translate information and instructions into the inspector’s language and subsequently translate inspection reports into English. This service is usually provided with a short time delay and at no additional cost; however, translation is a filter that can delay responses and make communication less transparent. This communication challenge can usually be overcome. Regardless, the project team should be aware of this challenge.

FACT: A project needs strategies and teamwork to manage inspection activities cost-effectively, especially when the inspector is inexperienced.

7. MYTH: The inspector has immediate access to all the procurement and supplier documents

Fifteen years or more ago, it was common for a project to courier printed materials to the inspector. This included a binder or folder with hard copy procurement documents, supplier drawings (EP-reviewed copies with comments, if any), and revisions. While this is a best practice, it is no longer feasible to use this method because of the benefits projects realize by using digital files. Digital files are much easier and economical for a project to produce, file, and transmit compared to hard copies that need to be printed, stored, distributed, transported, and handled. Today, hard copies are rarely produced. Typically, hard copies are provided as a special request or on an as‑needed basis.

Today and for this reason, inspectors are issued digital copies of selected documents and rarely (if ever) issued hard copies. Supplier documents are reviewed by the EP once or more and each document is issued with more than one revision during detailed engineering. The inspector does not require every project document (or its revisions, if any), so issuing every document to the inspector is not necessary. Thus, the SQS coordinator may send digital copies of selected documents with the inspection assignment when these are (re)issued or upon request. Today, hard copies are rarely provided, and only on an as-needed basis or as a special request.

An inspector conventionally does not have the resources to manage many documents, especially when they are engaged within two weeks of what may be the only inspection activity. An inspector often also typically lacks resources to print documents – particularly 11″ x 17″ or voluminous documents. The only exception is if the inspector has access to a print shop – but this is an additional expense for the project. The documentation may comprise hundreds or thousands of Megabytes or pages that the inspector simply does not have time to read or use.

Most experienced inspectors only need to refer to digital documents (e.g., specifications) for reference when addressing a specific challenge (e.g., marking and packaging requirements for shipment). It is inconvenient for an inspector to access digital files during inspection activities because files are stored on a laptop or tablet, and access to a clean environment for viewing files is a challenge.

This is key.

The procurement documents usually require the supplier to provide the inspector access to relevant hard copy documentation (e.g., drawings and quality records) for inspection purposes. Here is the rub – the supplier’s documentation is typically not marked with EP company comments and stamped with EP review codes. The documents provided are the same drawings used by supplier personnel for production. Thus, to prevent ambiguity, it is a best practice for the inspector to report document drawing numbers and revisions that were used for the inspection.

FACT: The inspector uses selected digital and hard copy documentation for inspection that is issued by the SQS coordinator, supplier, or a combination. Remember: inspection is a risk management not a quality management function — see Myth #1.

8. MYTH: An inspector’s acceptance of documentation or inspection results is final

An inspector will often inspect a product or review documentation, determine it is acceptable, and report it as such. An inspector is knowledgeable about acceptance criteria and usually competent to accept the results.

An Example

A hydrotest must be completed at a minimum specified pressure and for a minimum duration, with no pressure drop or signs of leakage to be acceptable. A project may deem an inspector’s acceptance of the hydrotest and its report sufficient.

Another Example

A pump performance test may be witnessed and accepted by an inspector. The supplier’s test report, however, is typically submitted for review by the responsible engineer. The responsible engineer may agree or disagree with the inspector or suppliers’ acceptance, based on specific criteria for the net positive suction head (NPSH), noise level, vibration level, or other requirements identified in the pump data sheet, specifications, or standards.

The final inspection and acceptance of a product at the supplier’s facility does not preclude the existence of a latent defect or the introduction of a subsequent defect during production or from handling, packaging, or shipment. All shipments to the final destination (e.g., site) must be subject to a receiving inspection. This includes the verification of acceptable condition, description, quality, and quantity of equipment, and material received, with a review of documentation on file that is corroborated with shipping documentation.

FACT: The responsible engineer or receiver at site is responsible for final acceptance of documentation and product, regardless of any previous acceptance by others.

9. MYTH: Inspection activities are limited to requirements identified in the inspection requirements document or inspection and test plan

The inspection requirements document (IRD) usually identifies the QVPs that are planned for a purchase order (PO) and the quality surveillance (QS) level, which informs the supplier of the duration and frequency of inspection visits. Some procurement documents may identify only one or the other.

The QVPs are incorporated into the supplier ITP using the supplier’s terminology, which may be different than the project’s terminology. If no QVPs are identified, these may be identified during the project team’s review of the ITP. For example, hydrotesting is identified as a witness point (this is the same as an API observation point).

There are, however, several other methods and sources of guidance for inspection activities:

- The inspection assignment may provide detailed instructions regarding inspection activities (to which the supplier is not privy) such as the precise duration and frequency of visits, non-witnessed activities or unscheduled visits (e.g., during the nightshift!), and other project concerns (e.g., lessons learned regarding documentation or materials);

- The inspection assignment typically requires that the inspector contact the SQS coordinator immediately from the supplier’s facility if there is a major concern (e.g., a non-conformance). The SQS coordinator may give subsequent instructions to the inspector at any time, such as a request to make additional visits, perform additional activities, or cease inspection altogether. It is a best practice for such communications to be made in writing (e.g., by a follow-up email) if the instructions were provided outside of project communication channels or verbally (e.g., by telephone call or text on a personal cell phone);

- The inspector will be knowledgeable about inspection requirements and relevant details that may not be identified in the IRD or ITP; and,

An Example

NDE is often required for welds to ensure quality per a code of construction. Client specifications for pressure equipment usually have more stringent requirements that supersede the code of construction. For example, a specification may permit a maximum of two repairs before the weld shall be cut-out and re-welded. This requirement may be avoided by a supplier that wants to save money or a welder that wants to avoid rework. The inspector can request that a defective weld be cut-out after a second repair. - Inspection provides the project with boots and eyes on the ground. The inspector may have previously worked with the client or project and be familiar with the supplier’s facility and its personnel. They can offer intelligent observations that enable the project team to manage challenges proactively.

An Example

An inspector can report that production appears to be about 25% complete and the schedule is inaccurate because it indicates production should be 50% complete. This may be because the supplier has resources (personnel) that are absent because of the prevalence of Coronavirus 19 (COVID 19) or focused on a different project. Yet, the supplier may report to the project that production is on schedule, even when it is obviously not. The supplier may have good intentions to make this work up by the end of the schedule; however, falsely reporting production progress puts the project schedule at risk and may have dire consequences for the project. Accurate information provided from an experienced, knowledgeable inspector means that the project can advise construction and other stakeholders accurately, expedite the supplier to meet their schedule, or a combination. This function is crucial to project success.

FACT: Inspection services are much more than the activities identified in the inspection requirements document or inspection and test plan.

10. MYTH: Inspection is a one-size-fits-all solution

Project differences (e.g., objectives, priorities, stakeholders, and risks) range from minor to substantial. Indeed, minor differences are inevitable on any project. Many factors influence SQS plans including changes to best practices, personnel, regulations, specifications, strategies, suppliers, systems, and technologies. A new project may have substantial differences, even if it is a copy scope project. See inset for a definition of copy scope.

These differences may include different:

- Client businesses (e.g., with the same or different business units);

- Client procedures and specifications;

- Client structures (e.g., as a single entity or joint venture);

- Complexities and costs of equipment and materials;

- Construction sites (e.g., local vs. international);

- EP corporate or project‐specific instructions, or both;

- Equipment and materials (e.g., made‐to‐order or custom vs. in stock or off‐the‐shelf);

- Project sizes (large vs. small), which affects the project strategy and timeline;

- Scopes (e.g., brownfield, greenfield, or a combination):

- Sectors (e.g., facility, pipeline, or power);

- Suppliers (e.g., in different countries and time zones); and,

- Supply chains (e.g., local vs. international).

These differences must be reviewed, considered, and addressed in detail at the beginning of a project (i.e., during detailed engineering). Project personnel must also update instructions, monitor results, and make adjustments throughout the project lifecycle. This is the basis of the plan‐do‐check‐act concept, a four‐step project planning tool used for continuous improvement. This applies to QS levels, QVPs, and other inspection requirements.

FACT: Inspection requirements may be similar for a new project, but differences must be reviewed, considered, and addressed.

Supplemental Information – Busting Two More Myths

The beginning of this article mentions that projects have hidden knowledge gaps because the project management BOK and SCM BOK contain no detailed information or how-to guidelines for SQS. Worse, and widening the gap, the SQS BOK is not published – it is only available as propriety IP and tribal knowledge.

These entities have and use proprietary SQS procedures:

- Major EPs, such as Bantrel/Bechtel, Fluor, Jacobs, Stantec, and Wood Group; and,

- Major project owners, such as ExxonMobil/Imperial Oil, Cenovus, Shell, Suncor, and T&C Energy.

Only their business partners and personnel have access to these resources.

Personnel who work as SQS coordinators typically have experience working with QC and the trades (e.g., coating, electrical and instrumentation, and welding). They may:

- Be certified as master electricians or welding inspectors, and have experience working as inspectors or QC managers, or both;

- Have on-the-job (OTJ) SQS training; and,

- Hold associate engineering degrees or technical diplomas.

SQS tribal knowledge is unwritten information that may or may not be commonly known by others within an organization or project. This knowledge may or may not be a best practice. Because SQS tribal knowledge is undocumented, it is prone to change and varies over time.

SUPPLEMENTAL MYTH 1: Project managers are knowledgeable about inspection

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®) states that inspection is performed as determined by the project team (8.1.2.6)[1]. There are other similar references that reiterate this; however, no detailed information or how-to guidelines are provided. It is the same for engineering educational curriculum – no detailed information or how-to guidelines are provided for SQS. Consequently, a project manager (PM) may not have any SQS training (unless it was offered by their employer). Some personnel may only have hands-on SQS training. Alas, there is no published BOK for SQS!

PMs may be experienced with, and knowledgeable about, general inspection requirements; however, rarely have hands-on experience coordinating inspection, identifying and resolving inspection challenges, or planning and preparing inspection assignments. Therefore, inspection methods, objectives, and strategies may be a mystery.

An Example

Engineering identified all the QVPs for the project. So, was an inspection services cost‑estimate prepared and approved on that basis? Or did project controls prepare a budget based on a percentage of the equipment and material cost or the inspection cost from the last project? Are the QVPs and the SQS cost estimate aligned? If not, someone will be disappointed, surprised, or both. To mitigate disappointment and surprise (reactions not welcomed by any project!), consult with the SQS coordinator when planning project requirements.

FACT: Inspection myths originate from a gap in the project management body of knowledge.

SUPPLEMENTAL MYTH 2: Supply chain managers or procurement managers are knowledgeable about inspection

The Competencies of Canadian Supply Chain Professionals is a BOK, which states that (for international trade) one must negotiate pre-shipment inspection (2.7.16 bullet #4)[2]. No detailed information or how to guidelines are provided. Similarly, for the Operations Management BOK[3] and business educational curriculum – no detailed information or how-to guidelines are provided for SQS. Consequently, a supply chain manager (SCM) or procurement manager may not have any SQS training (unless it was offered by their employer). Some personnel may only have hands on SQS training. Alas … again, there is no published BOK for SQS.

SCMs managers and procurement managers may be experienced with, and knowledgeable about, general inspection requirements; however, rarely have hands-on experience coordinating inspection, identifying and resolving inspection challenges, and planning and preparing inspection assignments. Therefore, inspection methods, objectives, and strategies may be a mystery.

An Example

How much will it cost to inspect a pressure vessel in Lloydminster, Alberta if there is no local inspector? When the QVPs were planned, did the project recognize that the inspector would need to travel (round trip) 550 km (340 mi.) from Nisku, Alberta for each visit? Does the project realize that inspector travel cost will greatly exceed the cost of inspection? How can the project prepare an inspection plan that is appropriate and cost effective? Damn the cost is not a sustainable model. To mitigate disappointment and surprise (reactions not welcomed by any project!), consult with the SQS coordinator when planning project requirements.

FACT: Inspection myths originate from a gap in the supply chain management body of knowledge.

Conclusion – Mind the Knowledge Gap

The London Underground (i.e., rapid transit system) in the United Kingdom uses the phrase mind the gap to warn passengers to use caution when stepping over the ubiquitous gap between the train and station platform.

There are other ubiquitous gaps of which to be mindful. For projects, these are gaps in the PM BOK and SCM BOK because the SQS BOK is only available as propriety information and tribal knowledge. With experienced and knowledgeable SQS coordinators and inspectors, and proper planning, a project can mitigate risk and ensure that equipment and materials are delivered complete, correct, and on-time.

Continuous learning is required for career success; it does not stop after graduation or obtaining a certification. More can be accomplished through teamwork than by individuals working alone. Projects succeed when collaboration and communication are used effectively and strategically to plan SQS and inspection requirements. Ultimately, they mitigate the risk that equipment and materials are delivered incomplete, incorrect, or late.

Read More

The KT Project

helps complex capital projects in the energy and other sectors implement best practices

for knowledge transfer and project communication. To learn more about effective

SQS, read this ebook:

Effective

Supplier Quality Surveillance (SQS) – Implementing programs on complex capital

projects

The KT Project Glossary

of Common Industry and Project Terminology is the first comprehensive

terminology resource written specifically for capital projects in energy and

other sectors. To learn more about effective project communication, read this ebook:

Successful

Projects Need Effective Communication.

Notes

This article was published:

- By the Oilman Magazine on 21-Feb-2021. https://oilmanmagazine.com/top-ten-myths-of-third-party-inspection/

- As an edited version, in the CWB Association WELD magazine, 2022 Spring edition. https://www.cwbgroup.org/association/publications/weld-spring2022

About the Author

Roy O. Christensen founded KT Project to save organizations significant money and time by providing key resources to leverage expert knowledge transfer for successful project execution.

Contact Roy to learn more about these useful resources:

- Roy O. Christensen

- [email protected]

- +1 403 703-2686

Figures

- Top Ten graphic. https://www.javelin-tech.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/solidworks-top-ten-list.jpg

- Inspection definition. definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Supplier quality surveillance definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Body of knowledge definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Procurement documents definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Quality verification point definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Copy scope definition. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- Quotations by Calvin Coolidge, John Heywood, and an anonymous source (African proverb).

- Mind the Gap graphic. https://i.pinimg.com/originals/91/9b/a5/919ba5f8a8ace19c283ab7ab383876e1.jpg

References

- Project Management Institute, Inc.. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th Edition. https://www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/foundational/pmbok

- Supply Chain Canada. The Competencies of Canadian Supply Chain Professionals, 1st Edition. https://www.supplychaincanada.com/media/reports/Supply-Chain-Canada-Competencies-Framework.pdf

- Association for Supply Chain Management. Operations Management Body of Knowledge (OMBOK) Framework, 3rd Edition. http://www.apics.org/apics-for-individuals/apics-magazine-home/resources/ombok

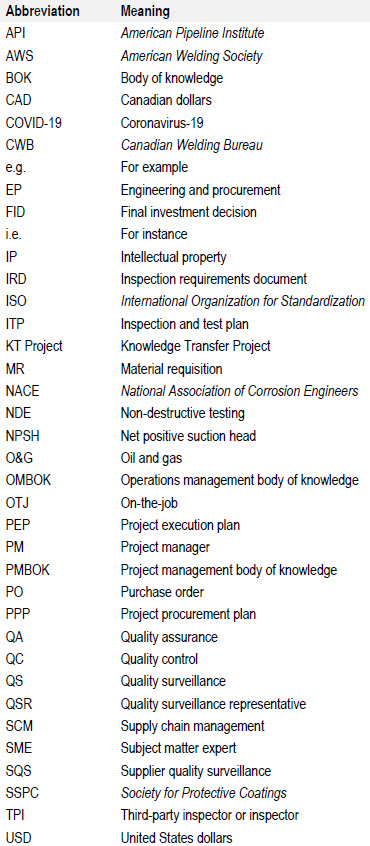

Abbreviations