What Learning Danish Really Taught Me

Worldwide, only 6 million people speak Danish. Why learn it? Because, while reaching the destination is rewarding, it is in the journey that we learn the real lessons. It is all about the journey. The lessons I learned from my journey culminated over decades. I used them to identify the need for, and then to write, the first glossary written specifically for capital projects in energy and other sectors. If this >700-page glossary is the destination, then this article summarizes the journey.

This article discusses my:

- Roots and upbringing in Standard, Alberta, Canada with a Danish-Canadian heritage (Section 1);

- Serendipitous preparation and moving to Denmark (Section 2);

- Total immersion living and working with Danes, and 14 biggest lessons (Section 3); and,

- Takeaway from the journey (Section 4).

1 A Danish Standard

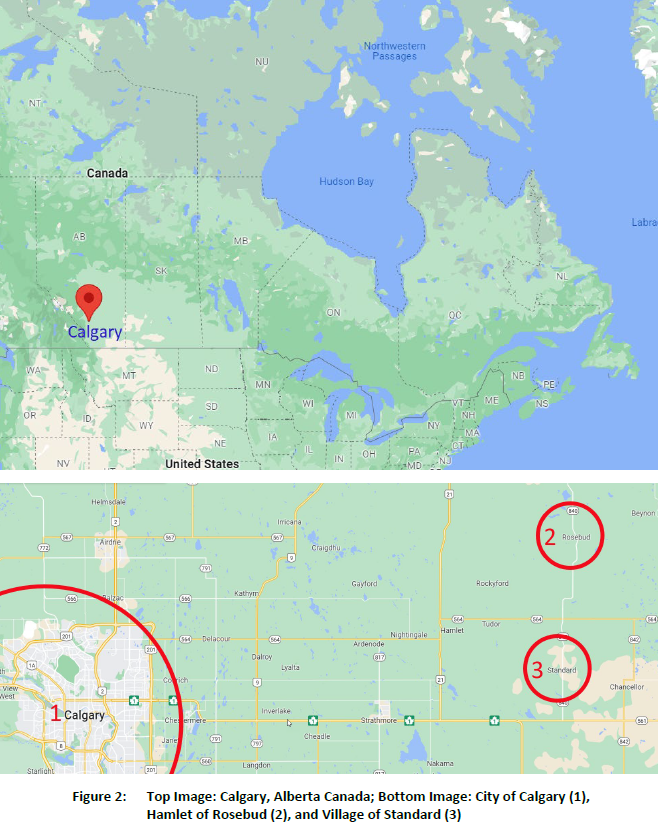

My grandfather (farfar or father’s father) Otto Dinfeldt (OD) Christensen emigrated from Denmark to St. Paul, Minnesota, United States in 1908 where some of his siblings lived. Later, in 1914, he and his brother Edward Christensen became pioneers when they purchased adjacent plots of land about 13 km (8 mi) from what would become Standard, Alberta, Canada.[1] Standard was incorporated as a village just eight years later in 1922 (see 3 in Figure 2). When they immigrated to Canada in 1915, Edward began farming near Standard. And OD broke farmland in Robsart, Saskatchewan with a turn‑of-the-century Rumley steam‑powered tractor. He returned to his land near Standard and began farming it in 1916. Find Edward and OD’s stories in From Danaview to Standard, which is a Standard area history book.[2]

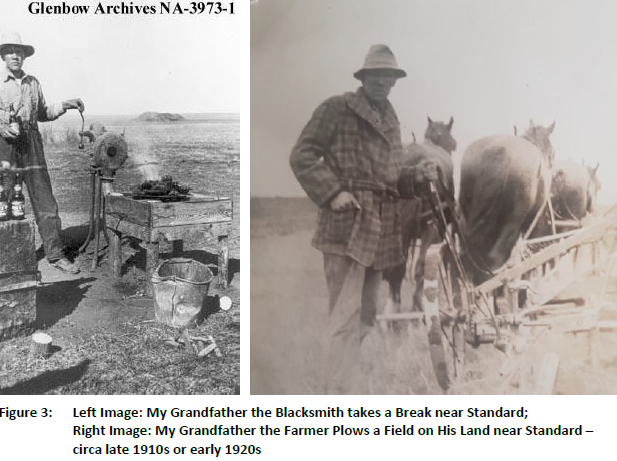

1.1 My Grandfather was a Blacksmith and Farmer

During Word War 1, my grandfather (Figure 3) was a blacksmith and mixed farmer (i.e., dairy and grain) who farmed his land from 1916 through the 1930s.[3] His son and my father, Oliver Christensen (Figure 4), was a grain farmer who farmed the land from the mid-1950s until the late 1980s. My grandfather and father became well‑known and earned respect for their service building the community, and their charitable and giving natures. My grandfather was instrumental in founding the South Valley School in 1919. He was a board member during almost all the years in which it operated. It closed in 1943. Similarly, my father was instrumental in founding the Rosebud School of the Arts (RSA) and the Rosebud Theater. See Section 1.2 for more about my father.

During the 1940s to mid-1950s and after the late 1980s, Edward’s family and neighbours farmed the land. Today, these lands are owned and farmed by Ed Christensen’s great-grandson – Craig Christensen. And a portion is owned and farmed by brothers Cam and Jon Wheatley.

1.1.1 My Grandmother’s Family Were Pioneers

My grandmother (farmor’s or father’s mother’s) Marie Reiffenstein’s family emigrated from Denmark to Garner, Iowa, United States at the turn of the 19th century, where she was born. She was a homemaker, mother, grandmother, and wife. In 1917, her father Andrew Reiffenstein and his brother Peter became pioneers when they purchased and moved to adjacent plots of land about 14 km (9 mi) from Standard. This land abutted OD and Edward’s lands. OD volunteered to pick-up the Reiffenstein family from the train station at Gleichen, Alberta and bring them to their farm using his horse-drawn wagon. Their fate was sealed: after first meeting on that day, Marie and OD were married five years later in 1922. They raised their family on their farm.

1.1.2 The Christensen Family Farming Legacy

Edward built a legacy in Standard; his family celebrated 100 years of farming in 2014. Their lands have been owned and worked by the same family for three generations. While somewhat common in Europe, this lengthy continuous legacy of farming is quite remarkable in Canada especially given the young age of the nation.

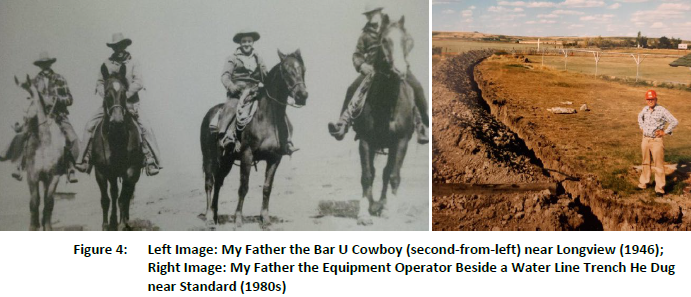

1.2 My Father was a Farmer and a Cowboy

My father (Figure 4) was born in my grandparent’s one-room farmhouse in 1924. My grandfather later constructed a second room in the farmhouse to accommodate a visit from his father Nels and stepmother, who visited from Denmark in the mid‑1920s. My father attended South Valley School (which was founded by my grandfather). The South Valley School was a one‑room schoolhouse located 1.6 km (1 mi) north of the family farm. My father spoke Danish in his home and only became fluent in English after 1930 by attending South Valley School. In 1928 my grandfather built a new two‑story farmhouse that still stands today. After this farmhouse was built, the old two-room farmhouse was returned to the land when my grandfather demolished it.

Like my grandfather, my father was also a farmer. But after World War 2 (from 1945 to 1947), he was also a cowboy or rider at the Bar U Ranch[4] located about 14 km (9 mi) south of beautiful Longview, Alberta in the foothills of the Western Canadian Rocky Mountains. He also could have been a baker because he loved making whole wheat bread with his own farm-grown wheat. He also made the world’s best Danish brunkager or brown cookies or spice cookies, which were better than could be found in all of Denmark. Apologies Denmark! I still love you for other reasons.

My father was a major driving force in the development of the nearby Rosebud hamlet community (see 2 in Figure 2), located about 36 km (22 mi) north of the family farm. My parents purchased and donated 16 hectares (40 acres) of adjacent land where the Rosebud Church and a Rosebud Theatre building now stand. Their generous philanthropy helped found the RSA[5] and renowned Rosebud Theater[6] – both of which still operate today. Throughout the 1980s, my father donated many years of his labour to his neighbours and community – making good use of his backhoe, truck, and wallet to selflessly build something substantive for future generations.

1.3 Growing Up with Danish Influences

Born to Oliver and Evelyn Christensen in 1961, I was raised on the farm near Standard, Alberta (see 3 in Figure 2), which is a village surrounded by Wheatland County about 90 km (55 mi) east of Calgary, Alberta. My childhood exposed me to Danish from an early age. Danish was, after all, my father’s native tongue and it was occasionally spoken in my parents’ home – especially when my parents hosted Danish-speaking guests. Many older generations in the community spoke Danish, which was so prevalent that a Danish newspaper was published in Standard for many years. My father was once chastised by his schoolteacher for joking with his cousin Charles (Chas) Christensen (Edward’s son) in Danish. The teacher did not understand their jokes or language and was not amused!

My family would regularly substitute English names of certain foods with Danish equivalents. Frikadeller was meatballs; rødkål was red cabbage; and kartofler was potatoes. When Danish‑speaking guests would arrive at our home, my father would say kom indenfor or come in! No other fathers would say this. Thus, as a child, this was both familiar and strange to me. When I travelled to Denmark as an adult in 1986, I again observed the familiar and strange. Written on chalkboard easels outside of some Danish pubs were the words:

- Kom indenfor! Menu: Frikadeller, rødkål, og kartofler.

- Come on in! Menu: meatballs, red cabbage, and potatoes.

But I get ahead of myself.

1.3.1 Visiting Denmark

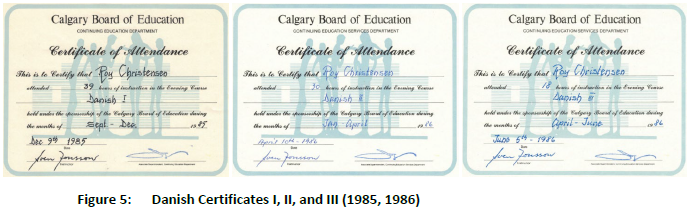

At only 12 years old, I visited Denmark with my family in 1973. And again at 14 with the Boy Scouts of Canada in 1975. My father’s heritage and use of Danish motivated me to learn more Danish. These visits to Denmark served to catalyze my motivation and passion for Danish culture. To this end, in the late 1970s I enrolled in a Danish class. And again in the mid-1980s. It is a wonderful experience to learn another language, especially when it is your father’s native tongue or one’s heritage language.

At the time, my single driving motivation was to learn the language spoken by my father. I just wanted to know it; my plan was not to travel and use it. This was partly because I never dreamed that I could live and work in Denmark. But that’s the great thing about a language. Once you know it, you can do both. I acquired Danish I, Danish II, and Danish III certificates by 1986 (Figure 5). It is great to have a goal because that is when the journey begins. Without a destination, there is no journey. Without a destination, there is no purpose.

2 Serendipitous Preparation: Moving to Denmark

2.1 A Visit from a Danish Cousin

During the summer of 1986, my second cousin Astrid Bendixen and her husband visited our family in Canada from Denmark (Figure 6).

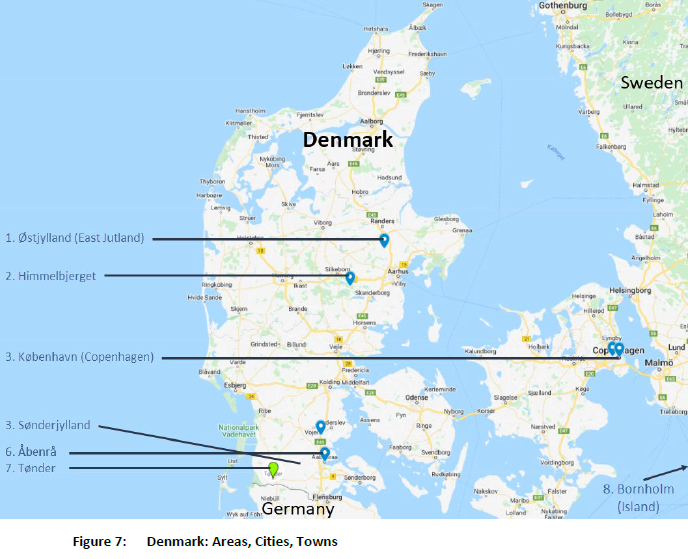

When they learned that I was a welder, they mentioned that the boilermaker[7] – Burmeister & Wain Energi A/S (BWE)[8] – in their town of Tønder (See 7 in Figure 7) had difficulty recruiting welders because of its southernly location on the Danish mainland in Sønderjylland (Southern Jutland). See 4 in Figure 7.

2.2 Basic Skills Already Acquired!

The motto of the Boy Scouts of Canada is Be Prepared. Even though I had not been preparing for this experience, I found myself already prepared. Serendipity! By 1986, at only 25 years of age, I had the ability, basic language skills, desire, passport, resources, and savings to move to, and work in, Denmark. By 1986 I had completed my welding apprenticeship in Alberta, and obtained Red Seal Journeyman Welder and Alberta B Pressure Welder certifications. Having only lived on the family farm, and briefly in Rosebud and Calgary, I had a strong desire to travel and see the world outside of Alberta. Astrid’s comment was enough to persuade me to act.

2.3 Moving to Denmark

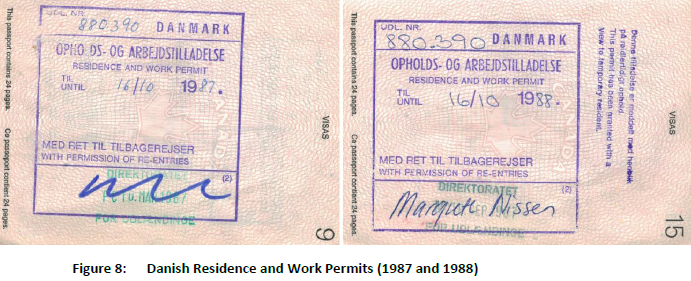

In September 1986, I bought an airline ticket and travelled to Denmark. A few days later, I visited BWE to complete a welding test. Afterwards, the quality manager examined and tested my weld. It seemed like the test replaced the interview because there was no formal interview! Then, I was informed that my first day at work would be the following Monday! And just like that, I became a welder living in Denmark! Figure 8 are my Danish residence and work permits.

2.4 Overcoming the Language Barrier

Speaking very basic Danish and living and working in Denmark are two very different things. But this was not a challenge. All BWE drawings and welding procedure specifications were written in Danish, German, and English. To ease my burden, thankfully, many of my co-workers also spoke English. I performed various welding tasks and enjoyed every minute. By immersing myself in the culture and country for the next two years (1986 to 1988), my knowledge of Danish grew everyday. Figure 1 is yours truly in Himmelbjerget, Denmark (see 2 in Figure 7) in 1987.[9]

3 Total Immersion: Living and Working With Danes

The best and fastest way to learn a language is to totally immerse yourself in it.

3.1 Learning Danish

Initially, I needed everyone to speak English to me. This worked out well because Danes wanted to speak English to me. They either enjoyed speaking it or showing off their English skills! However, after the first few months, as I slowly began to learn spoken Danish, I began refusing to speak English and instead spoke Danish exclusively (which would force my listeners to speak Danish). Eventually, after about six months, I was the one fluently speaking Danish and showing off my Danish skills!

Danish is a difficult language to learn. But this is not true for everyone. For example, those who cannot speak English as a first or second language or only understand an alphabet that is different from the English/Danish alphabet (e.g., Cantonese, Farsi, or Russian) struggle more that those who can. Because I am a native English speaker and know this alphabet, learning Danish had fewer challenges.

At first, I found that the Danish guttural sounds were most challenging to reproduce. But Danish grammar and pronunciation came naturally to me. This is because rigsdansk or Danish of the Realm has many similarities to Canadian English. For example, Canadian English and Danish do not use heavily‑accented words. Once I asked to be given a difficult Danish word to pronounce and was given the word universite or university. Ha! Its pronunciation and spelling are almost identical in English! Easy.

3.2 Influences and Dialects

Rigsdansk is to Denmark as Queen’s English is to England. Today, most Danes speak rigsdansk. Historically, Denmark had a number of regional and local dialects. One dialect is Sønderjysk or Southern Jutlandish, which is to Denmark as Newfoundland English is to Canada. Sønderjysk comprises many unique grammatical and phonological nuances. To me, the Danish in Sønderjylland – which abuts the Danish-German border in the south – sounded somewhat like German. And in København (see 3 in in Figure 7), near Sweden in the east, Danish sounded somewhat like Swedish. In other Danish places, dialects made the language sound completely different to me.[10] Location greatly influences language and dialect. This is true everywhere and has been for recorded history.

Another major influence on Danish is television.[11] Danes regularly watch television from other countries and therefore become familiar with German, Norwegian, and Swedish languages. I did not have a television while living in Denmark. This was unfortunate because, in Denmark, most programming (including Danish) has subtitles, which is very helpful to those learning Danish.

On weekends I travelled much of Denmark as a tourist and to visit

family and friends, including friends who were German, Iranian, and Polish. I

learned to speak Danish from Danes and people of diverse backgrounds. Hence, some

of the Danish I learned was accented with influences from foreign languages and

imperfect. I learned new expressions and words everyday, even though I had

difficulty pinpointing the source of most accents and dialects. I absorbed all

the Danish I could learn and, at first, completely butchered the language! If

you want an omelette, you need to break some eggs or æg. I broke a lot

of æg.

3.3 Key Achievements and Experiences

This section describes my memorable achievements and experiences while learning to speak Danish.

3.3.1 First Confidence Builders and Victories

Some of my more interesting first confidence builders and victories included:

- Purchasing a train ticket from København (Copenhagen) to Tinglev, to travel to Tønder.

En billet til Tinglev, tak or one ticket to Tinglev, please! - Listening to someone speak Danish, which I could understand before I could speak Danish. This was because I began to understand Danish before I could speak it;

- Cursing at panhandlers in the city of København and telling them I was a fremmed arbejder or foreign worker, and to get a job and earn their own damned money;

- Being asked how many years I had lived in Denmark, after nine months, because I spoke Danish fluently; and,

- Arguing with a Danish border guard about bringing a German rental car and too much tobacco across a border designated for Danish and German nationals only. I won the argument by arguing in Danish. I crossed the border without any fines. They told me not to come back. I did not return.[12]

3.3.2 My Journey’s Biggest Lessons

My journey living and working in Denmark taught me how communication and understanding can be difficult. This is true with different languages, such as Danish and English. And it is also true with different dialects and vernacular. I learned that this challenge also applies to business and project terminology. I learned 14 lessons about how to communicate effectively personally and in business by being mindful of the understanding of a message by the receiver or sender, and the context in which the message is communicated:

(1) Ask for clarification when there is potential for misunderstanding or miscommunication.

When learning a new language, a common frustration is the inability to understand information or instructions. It is always a bad idea to ignore the misunderstanding or pretend everything is understood. One of the earliest and most useful Danish phrases I learned was hvad betyder det or what does that mean?

Don’t be afraid to ask questions that clarify meaning.

(2) Sometimes the same thing has different names. Sometimes different things have the same name.

Ordering a Danish pastry in English at a restaurant in Denmark may confuse the waiter (at least briefly) because, while most Danes understand what Danish pastry is (in English), the name used by Danes is Wienerbrød or Vienna bread. But in Germany it is called Copenhagener. Same thing; different names.

Learn the names of the same thing and the things of the same name!

(3) The language used to communicate understanding must be suited to the audience. In Denmark this is usually Danish. But outside of Denmark, it almost certainly is not.

Once, one of my Danish language classmates exclaimed that, compared to English, Danish has a different word for everything – which is both profound and silly. Of course, another language uses different words for different things! How could it not?

In Denmark, children learn Danish from birth. In school, they learn English starting at age 11 and German at age 14. Many also learn another elective language such as French or Spanish. Hence, a substantial number of Danes are at least functionally trilingual. Demark is a small country with a population of <6 million that recognizes the need to communicate with others, in their language.

Consider your audience and their language when you communicate.

(4) Be creative and have fun while striving to reach goals.

Soon after arriving in Denmark, when attempting to register for a Danish-as-a-second-language class, I learned that only two Danish classes were available. Neither were suited to my level of understanding. The first class was for immigrants who spoke no Danish at all – it was too elementary. The second class was for Germans who spoke Danish but wanted to read and write Danish – it was too advanced. So, I did the only reasonable thing: I signed up for both classes. In one, I was the most advanced student; in the other, I was the least advanced. This was a great experience. In the first class, I helped others learn (the best way to learn is by teaching). In the second class, I needed others to help me learn (the second-best way to learn is to surround yourself with knowledgeable people). While unconventional, it was a fun and creative way to learn Danish. It gave perspective that would have been impossible in a single conventional class.

Use creative means to accomplish your goals.

(5) Being unable to speak in the audience’s language may mean communication is impossible.

During a visit to Denmark in 1975, my friend and I stayed for one week at his moster’s or mother’s sister’s or aunt’s home in København. One day, we visited a store to purchase buttermilk. We did not know the Danish word kærnemælk, so we used the literal translation from English, smørmælk. Nobody understood what we wanted; hence, we went home empty‑handed.

Speak the language that the audience will understand; doing otherwise is futile and a waste of time.

(6) Learn from the mistakes of others.

When I heard Danes making grammatical mistakes in English, I copied their errors to speak Danish correctly. For example, in English much money (singular) is correct while many money (plural) is incorrect. In spoken Danish, money is plural and thus the phrase many money is correct (mange penge).

There is more than one way to learn from the mistakes of others.

(7) There is more than one way to acquire knowledge.

In addition to taking the Danish classes mentioned in 4 in this list, I also took a German class to learn Danish! The class was introductory, so the teacher would speak about 30 Danish words for every 3 German words. Many German words are like Danish words, so I learned more Danish and some German. For example, auf passen in German means pas på in Danish – which means be careful.

Knowledge can be acquired everywhere.

(8) Do not assume you know what others know or understand.

Danes would immediately recognize me as a foreigner because of my accent. But they would often assume I was German and hence, would speak German to me. I would respond in Danish: jeg er ikke Tysker or I am not German and continue speaking Danish. This was usually met with surprise. No one would guess I was a Canadian fluent in English and not a German. They assumed they knew where I was from and what language I spoke. And even though I may look somewhat German, they were incorrect. And their incorrect assumptions guided their actions.

Making assumptions is always a bad idea. Do not make assumptions.

(9) Humour is useful for learning and remembering knowledge.

The Danish expression god dyr er råd or good advice is expensive is easy to understand in English. But in Danish, these words have two meanings:

- Dyr means animal or expensive; and,

- Råd means advice or rotten.

Hence, the Danish expression may be twisted to say and mean god dyr er råd or good animals are rotten. This expression means that there are no good animals –an expression from a bygone time when six horsepower actually meant using six horses.

(10) Sometimes a textbook is more useful on a shelf to support a bookend or as a paperweight than as a source of knowledge.

Once, I attempted to discuss the Danish city of Åbenrå (see 6 in Figure ) located in Østjylland or East Jutland (see 1 in Figure 7). I pronounced it clearly – exactly as my textbook instructed. The letter å is pronounced like the aw in law. They did not understand me. But I was speaking clearly and correctly. So why could they not understand? Åbenrå? Åbenrå? Åbenrå? Later, I noticed that the text book was published in the United Kingdom. The pronunciation was described for British English speakers, not Canadian English speakers! For a Canadian, the correct description is to pronounce å like the ow in row. If you are going to use a textbook, be sure to choose one that is appropriate for your purpose or understanding. Street or tribal knowledge is often more accurate than documentation or textbooks because it is current. Whereas, other resources become outdated or completely inapplicable.

One textbook is no panacea for learning.

(11) Even an experienced or knowledgeable person may need to confirm understanding.

Sometimes it felt like, for every word I learned in Danish, I forgot a word in English. Today, decades later, I can still easily remember the word sild but regularly struggle to remember its English equivalent (herring). Knowledge can be foggy or forgotten for many reasons; it is human to err. See also, 1 in this list.

Confirm and reconfirm understanding frequently.

(12) New knowledge is always being developed but old knowledge is the foundation.

During my childhood, I remember hearing my father and the older generations speaking Danish. This was exotic and unintelligible to me. During the summer of 1987, my father and sister Ruth Christensen visited me in Denmark. By that time, I could speak fluent Danish. For the first time in my life, I could speak with my father in Danish. It was rewarding and strange!

It was rewarding because my father could hear me speak his native tongue for the first time. It was a strange because he spoke Danish like his parents did when they emigrated around the turn of the 19th century. It was old Danish. His Danish was not rigsdansk. It sounded like it was from another era because it was. Nonetheless, even using new and old dialects, we understood each other.

We are standing on the shoulders of giants. Respect the authority of old knowledge and use this foundation to foster new knowledge for future generations.

(13) Transferrable skills are extremely valuable.

Scandinavian languages are largely mutually-intelligible so communication between Scandinavians is possible. The languages are more similar in writing than in speech because speech is more fluid. Danish is the official language of Denmark, the Faroe Islands, and is the second language in Greenland and Iceland. Danish is more like Norwegian[13] and less like Swedish[14]. And Swedish is the second language of Finland[15]].

When my friend Javad Rahimi immigrated to Canada from Sweden in the mid-1990s, he spoke only Farsi and Swedish. During conversations, I spoke Danish to him and he spoke Swedish to me until he had learned to speak functional English. By speaking Danish to my friend, at first, I helped him learn English.

Learn transferrable skills because they will serve you well in the future. Keep them in your pocket. And pull them out when you need them.

(14) Jargon and slang frustrate communication.

Swedes found it easier to understand me speaking Danish than the Danes! This was because I spoke in simple sentences, slowly, and used no jargon or slang. Jargon is abbreviations, expressions, and specific words used by a group or profession, which are difficult for others to understand.[16] Communication must be suited to the audience, as mentioned in 3 in this list.

Avoid jargon and slang whenever possible.

4 What Learning Danish Really Taught Me

Over 35 years have passed since I lived and worked in Denmark. After returning to Canada, I acquired a Welding Engineering Technology Diploma from Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) in 1990. Since then, I have worked as a technologist on energy and industrial projects:

- As a mechanical and welding inspector; and,

- Since 1998, as an inspection or supplier quality surveillance (SQS) coordinator.

When working for decades in the same discipline, patterns and repetition become apparent. Many of the lessons I learned from my Denmark experience were prevalent and kept repeating. Perhaps most prevalent and persistent was how common it was to find the obstacles of miscommunication and misunderstanding blocking project success. Often, these obstacles are like debris from an avalanche that block a critical path. Miscommunication has the ability to completely halt progress. Sometimes, it seems like project personnel are speaking different languages. And believe me, sometimes this is true literally and figuratively!

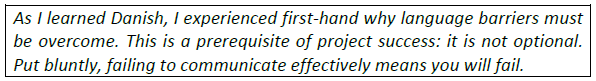

As I learned Danish, I experienced first‑hand why language barriers must be overcome. This is a prerequisite of project success: it is not optional. Put bluntly, failing to communicate effectively means you will fail. And this is what learning Danish really taught me.

Even the Construction Industry Institute[17] agrees that industry lacks a common language [and that] companies use their own terminology – which can be very confusing![18] Moreover, Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters[19] identified that detailed how-to guidelines are needed to improve project communication.[20] Unfortunately, neither they, nor the parties that require these guidelines, have produced anything of note. Like my Danish-English and English-Danish dictionaries, terminology needs to be defined to guide readers and speakers. Common understanding is needed to communicate effectively. And this understanding needs to be recorded in a document like a glossary.

Unlike a dictionary, which is overly-broad and general, a glossary is a single authority that defines select business, company, industry, and project terminology. A well-written glossary increases understanding of common terminology and provides a forum for all readers (from beginners to experts and those with English as a second language) to become informed and improve communication individually and as a group.

By drawing on over four decades of experience, I have spent the last four years writing the Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology.[21] It provides comprehensive current definitions for thousands of current energy and industry terms. At over 700 pages and 250,000 words, it is the first comprehensive terminology resource written specifically for capital projects in energy, industrial, mining, petrochemical, pipeline, power, and other sectors. This work provides reliable, dependable guidance for businesses and industry professionals. It is the product of my journey that could only be yielded after reaching my Danish and professional destinations.

This resource is a legacy document that will support professionals long into the future, when I am no longer able or willing. When this happens, I will return to Denmark to wander the beach as my giant grandfather did in 1970 and ponder my journey as he did his … 60 years later. I will look for his footprints.

Contact Roy Christensen (Section 9.1) to acquire this useful glossary.

5 Figures

- Roy O. Christensen collection. Roy O. Christensen: A Young Canadian Welder at Himmelbjerget, Denmark (1987).

- Google Maps. Top Image: Calgary, Alberta Canada; Bottom Image: City of Calgary (1), Hamlet of Rosebud (2), and Village of Standard (3).

- Roy O. Christensen collection. Left Image: My Grandfather the Blacksmith takes a Break near Standard; Right Image: My Grandfather the Farmer Plows a Field on His Land near Standard – circa late 1910s or early 1920s. (Also, Glenbow Museum Archives. Blacksmithing. http://ww2.glenbow.org/dbimages/arc10/c/na-3973-1.jpg).

- Roy O. Christensen collection. Left Image: My Father the Bar U Cowboy (second-from-left) near Longview (1946); Right Image: My Father the Equipment Operator Beside a Water Line Trench He Dug near Standard (1980s).

- Roy O. Christensen. Danish Certificates I, II, and III (1985, 1986).

- Google Maps. Denmark and Surrounding Countries.

- Google Maps. Denmark: Areas, Cities, Towns.

- Roy O. Christensen. Danish Residence and Work Permits (1987 and 1988).

6 References

- Standard was originally settled by Danish immigrants beginning in 1910. On August 13, 2022, Standard will celebrate its centennial anniversary.

- Standard Historical Book Society. From Danaview to Standard. Calgary, Alberta: Friesen Printers, 1979.

- At age 85 (in 1970), my grandfather returned to Denmark over 60 years after he emigrated to Canada. Walking on a beach near Esbjerg in Vestjylland or West Jylland, he happened to meet a stranger – another older gentleman – and they spoke. My grandfather must have enjoyed speaking Danish in Demark again (and eating Danish Wienerbrød, but that is another story!). My grandfather told the man he was a Canadian farmer visiting his fatherland. The other man said he had worked in Canada, many years before, for a Danish-Canadian farmer, near Standard and the farmer’s name was OD. This man worked for my grandfather in Canada, likely sometime in the 1920s – about 50 years earlier! My grandfather’s farm was about 7,100 km (4,400 mi) away. He was no stranger!

- Today the Bar U Ranch is a National Historic Site. At its peak, it was the largest ranch in Canada – extending over 64,750 hectares (160,000 acres) and was home to 30,000 cattle and 1,000 Percheron horses. Learn more at https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/ab/baru. Read about my father’s experience as a Bar U rider (and my grandfather’s story) in To Be a Cowboy: The Oliver Christensen Story, which was published by the university of Calgary (U of C) Press in 2004 when my father was 80 years old.

- The Rosebud School of the Arts is a guild school that provides post-secondary theatre training within a community of professional working artists. It continues to operate today. Learn more at https://www.rosebudschoolofthearts.com/

- Rosebud Theater productions feature professional live theatre that illustrates the beauty and complexity of life through an inclusive and grace‑filled perspective, while mentoring the next generation of theatre artists. It continues to operate today. Learn more at https://www.rosebudtheatre.com/

- Boilermakers build, erect, repair, test and maintain all types of boilers, tanks and pressure vessels, and perform structural and plate work on dust, air, gas, steam, oil, water and other liquid-tight pressure containers. Source: https://alis.alberta.ca/occinfo/occupations-in-alberta/occupation-profiles/boilermaker/

- In 2017, BWE was acquired by Burmeister & Wain Scandinavian Contractor A/S.

- Located in the Østjylland or East Jutland area of Denmark (see 1 in Figure 7), Himmelbjerget or Sky Mountain (see 2 in Figure 7) is one of the highest natural points in Denmark (147 m), which is remarkable from a Danish perspective.

- Elderly Danes in Sønderjylland are often more familiar with German than English. This is because Sønderjylland was under German rule after the 1864 war. Later, in 1920, it was returned to Denmark after a referendum following the defeat of Germany in World War I. In 1955, the Danish and German governments agreed to legislative measures that protected respective minorities on each side of the border against discrimination. Thus, representatives from a Danish political association continue to be elected to the local parliament in the Schleswig‑Holstein region in Germany. Much earlier, before 1864, this region was ruled by the Danish monarchy.

- Since the 1960s, access to higher education and urbanization have reduced the use of dialects in everyday spoken Danish. Nonetheless, some dialects survive in relative isolated communities, such as on the island of Bornholm (see 8 in Figure 7).

- At that time (1987), Danish citizens were not permitted to rent a car in Germany and drive it into Denmark. The car was rented by my father and driven by me, a Canadian citizen. Thus, I knew the law would not apply to me. Foreigners were permitted to bring more tobacco (which was heavily-taxed) into the country than Danish citizens. I knew the law and the maximum legal amount.

- Norway was under Danish rule for almost 400 years until 1814. It was overtaken over by Sweden and governed under the Swedish monarchy until 1905. When the Norwegians chose to establish their own monarchy, they selected a Danish prince and approved his role through a referendum.

- The region of Southern Sweden called Skåne was ruled by Denmark for centuries until 1658, when Denmark lost a war to the Swedish Army and were forced to abandon the region. Many inhabitants in Skåne are familiar with Danish; many Copenhageners are familiar with Swedish.

- Swedish is the first spoken language of about seven percent of the Finnish population.

- KT Project. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

- The Construction Industry Institute, based at The University of Texas at Austin and founded in 1983, is a consortium of more than 140 leading owner, engineering-contractor, and supplier firms from public and private arenas. It is the research and development centre for the capital projects industry.

- Construction Industry Institute. Achieving Zero Rework Through Effective Supplier Quality Practices. https://www.construction-institute.org/resources/knowledgebase/best-practices/quality-management/topics/rt-308/pubs/rs308-1

- The Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters, established in 1872 by an Act of Parliament, is Canada’s largest trade and industry association. It is the voice of manufacturing and global business in Canada.

- Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters. Oil Sands Manufacturing. https://cme-mec.ca/

- KT Project. Glossary of Common Industry and Project Terminology. www.ktproject.ca

7 Learn More

To learn more about effective communication and project success, read this KT Project eBook: Successful Projects Need Effective Communication.

8 Notes

- This article is dedicated to the memory of:

- My grandfather and father who taught me my first Danish words, and provided advice and knowledge that has guided me over a lifetime; and,

- Birgit Reiffenstein Bürger (my father’s second cousin) for her incomparable hospitality and teaching me the most Danish culture, history, and language.

- The article was peer-reviewed in March 2022 for accuracy by Flemming Ytzen, a Danish author and journalist. https://flemmingytzen.com/

9 About the Author

Roy O. Christensen founded the KT Project to save organizations significant money and time by providing key resources to leverage expert knowledge transfer for successful project execution.

9.1 Contact

Roy O. Christensen

Email: [email protected]

Telephone: +1 403 703-2686